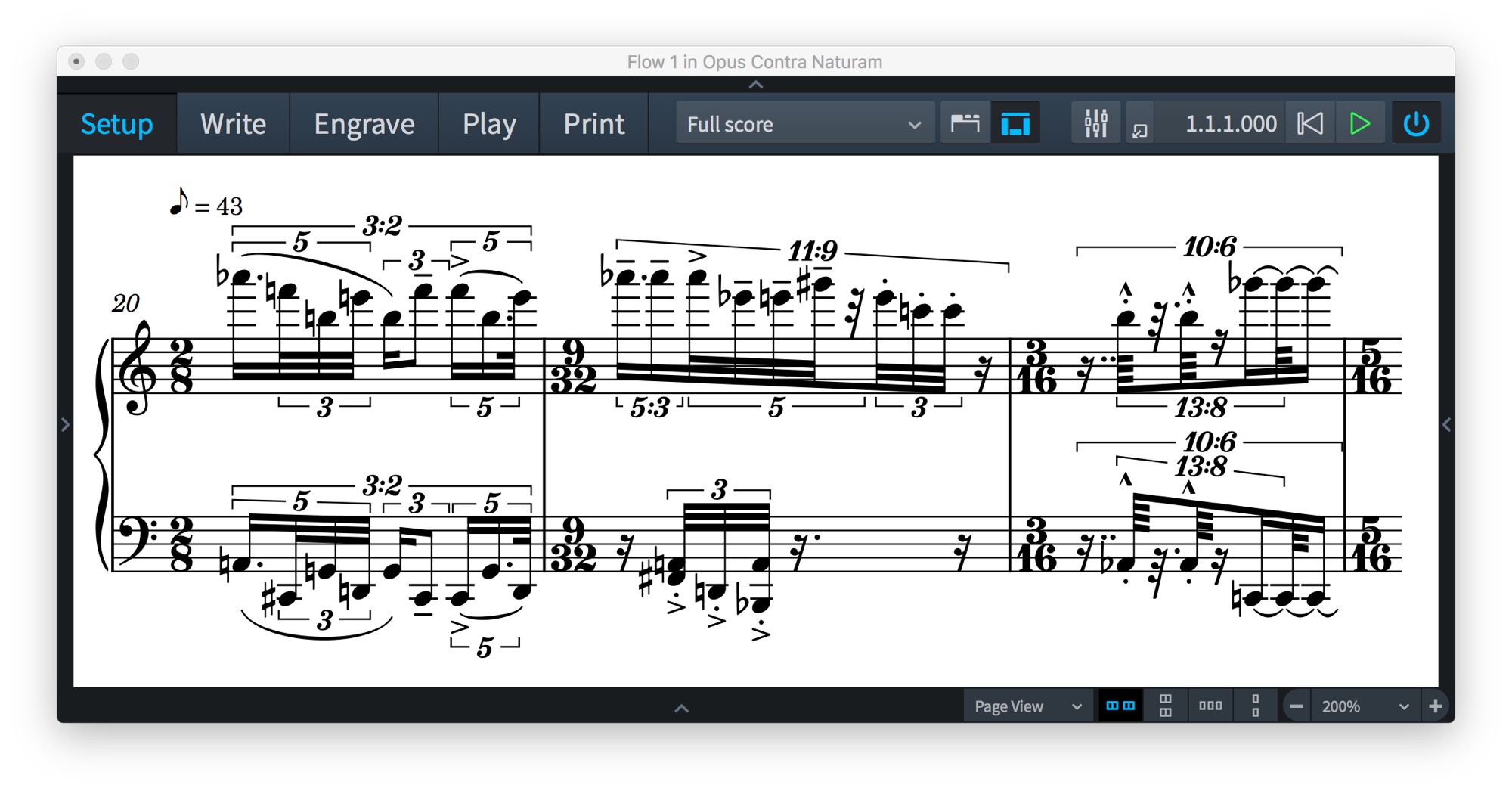

One month ago, after following its development from a distance for a year or so, I downloaded a free trial of Dorico. And today, when my trial expired after a thirty-day test drive, I immediately purchased a license. Dorico has exceeded my expectations in every way, and it’s already changing the way I write and arrange.

You can find out more about Dorico here, and here, and here, and peer behind the curtain here. Rather than rehash what others have written, I thought I’d share my experiences with it as an arranger and composer.

If it’s broke, fix it

Finale has a comforting familiarity for me, especially as my usage has increased over the past ten years. After all, people don’t know what they like; they like what they know. Use any program long enough, and you’ll become proficient enough to make it do what you need it to do. Pick a path and stick to it. And my experience confirmed that: I had amassed plug-ins and expression libraries and shortcuts and workarounds, and I was moderately pleased with everything. I had no expectation that I’d ever move away from Finale. Besides, novelty alone is never a good reason to do much of anything, especially something like changing one’s professional workflow.

Hello darkness, my old friend

But two concerns were growing in my mind. The first was the trajectory of MakeMusic, the company that owns Finale. Although the bug fixes have continued at a respectable pace, Finale feels like a 30-year-old program. That’s not necessarily a weakness in every context, but Finale has amassed a pile of technical debt, an accumulation of decades of old code that makes it nearly impossible to improve core functionality. And, with a lion’s share of the educational and professional market, the company seems to have settled into a holding pattern. So it should come as no surprise that, with its recent release of version 25, Finale is just now entering the world of 64-bit compatibility. And it still doesn’t fully support high-DPI monitors. Apparently Finale is content to react to existing technology slowly, and to abandon innovation almost entirely.

If Finale worked perfectly, innovation wouldn’t be all that important. But the second and more basic problem I have with Finale is that some things—many things—just take too long. This is the double-edged sword of familiarity with any particular program: it increases efficiency but breeds complacency. You start to assume a priori that the workflow you have is the best it can be. But it was a year or so ago, while making hundreds of agonizing manual adjustments to orchestral parts, that a nagging realization was dawning in my mind: What if all this work isn’t necessary?

Something feels vaguely wrong here.

Although I was slow to admit it, the reality was that my workflow in Finale was never satisfactory. If you divide the arranging or composing process into “the creative part” (putting ideas to the page) and “the practical part” (score details and layout), you realize they have very different requirements… but both are necessary. And to me, Finale was failing at both. I felt continually stymied in the creative process by Finale’s metrical demands. And when I did finish setting my thoughts to the page, I knew that, no matter my proficiency, it would be at least an hour of moving and nudging and tweaking the score to make it print-ready for real musicians to use.

Enter Dorico. I first looked into it nine months after its release, but it didn’t seem ready to me, and I wasn’t interested in being an early adopter. And then life slowed down this past June, and I took a second long look at the newly-released Dorico 2.

Learn, then do

I knew if I just jumped into an entirely different notation program with no preparation, I’d quickly be stymied and give up. People like what they know, remember? I grew up listening to Gardiner’s recording of Beethoven’s Fifth, so to this day, everyone else’s interpretation sounds too slow to me. I knew I had to be willing to start from scratch in order to give Dorico a fair shot, rather than trying to click and type with a Finale brain and try to compare it to what I knew.

So for two weeks, I binge-watched the YouTube tutorials. And I memorized the keyboard shortcuts. It was enjoyable, actually. The videos are well-made, the pace is good, and the narration is done with a British accent (that’s a bonus). After two weeks, I felt like I knew the program without having even installed or opened it. And when I finally did set up a new project and start writing, it just worked.

After transcribing a handful of projects, I just finished my first orchestration in Dorico last week, from first sketches to finished scores. Here are my thoughts.

Composing is easier

My first observation from using Dorico is that it is already changing the way I compose and arrange. That hadn’t been my goal; I was mostly expecting to save time in the detail/layout phase. But my experience turned out to be a classic case of “You don’t know what you don’t know.” I knew I didn’t like to compose in Finale, but I didn’t realize how much better it could be.

There are two basic categories of compositional workflow in Dorico that are drastically different from Finale:

1. Notes are events that you place on a grid.

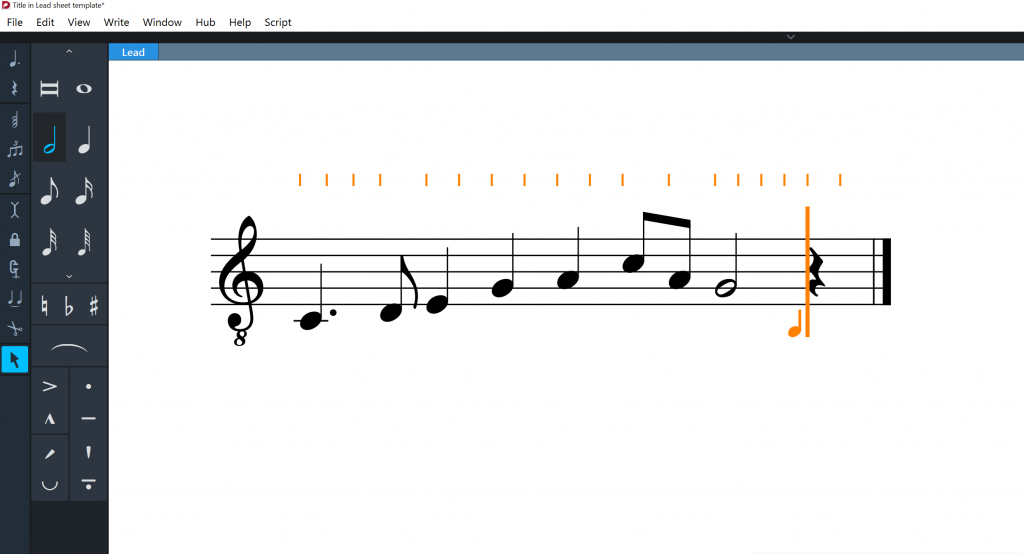

Much like using manuscript paper, you can just start entering notes:

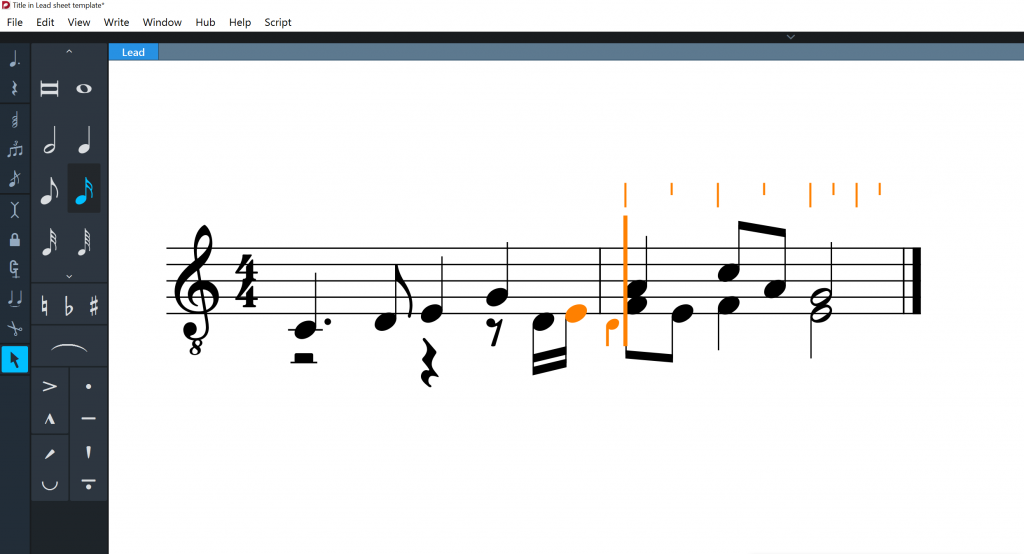

Dorico operates on a rhythmic grid, and you can easily change the unit value with a key command (here it’s set to eighth notes). If you want to enter a second voice, move the caret to the spot you want, hit Shift+V (to create a new voice), and go:

The rests are added as needed (and you can hide them if you want).

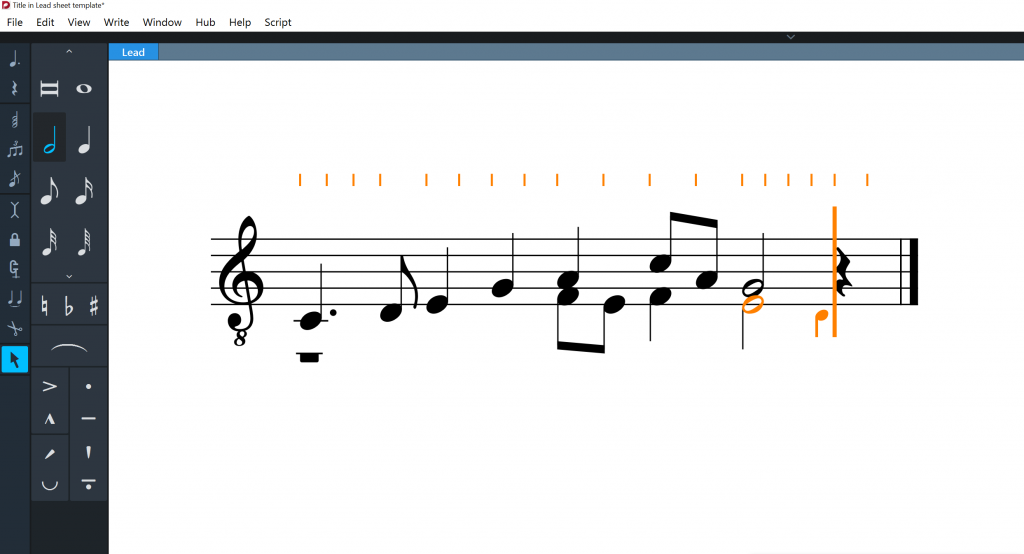

Now, here’s where Dorico helps keep the compositional process moving forward. I can retrofit the existing musical example with a time signature (without using the mouse to click through menus. Just type Shift+M for the meter “popover,” type 4/4, and press enter). But what if I wanted to add a sixteenth-note pickup to voice 2? No need to delete rests or shift things around. Just move the caret to the spot on the rhythmic grid and start inputting your notes:

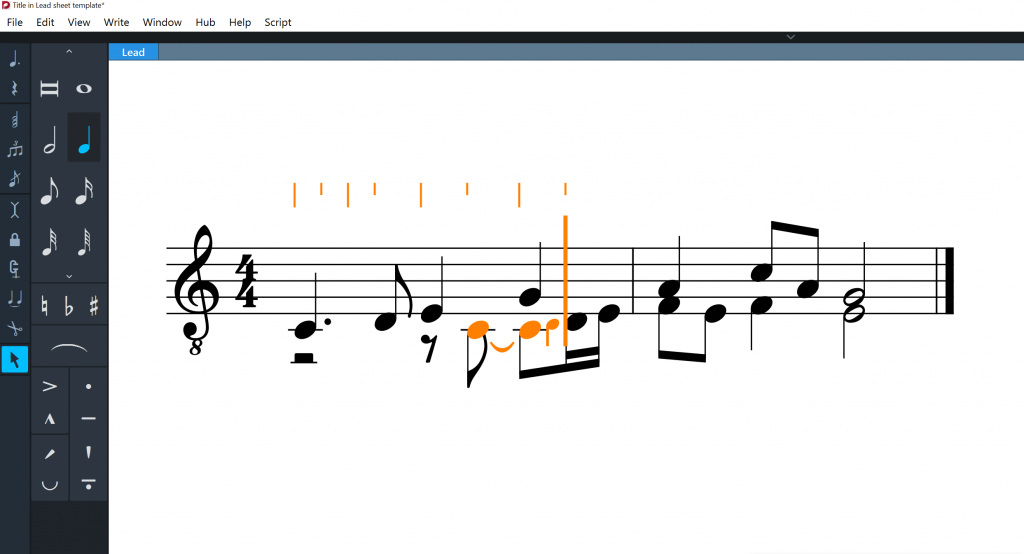

And suppose I then decide to add a syncopated quarter before that. Just move the caret back and enter, not an eighth tied to an eighth, but… a quarter note:

The effect here is incalculable. In Finale, you must first make room for your ideas. It’s akin to running into the ER and being asked to fill out paperwork before you can be treated. In Dorico, just write your ideas down. Game changer.

You can see above that Dorico receives instruction regarding duration (quarter note) and notates it according to its position in the meter (tied eighths). Here’s another example:

In Finale, you’d need to enter each of these values as written, with ties. But in Dorico, you can enter them as a string of dotted eighth notes (and if you really want dotted eighth notes, you can force Dorico to do that).

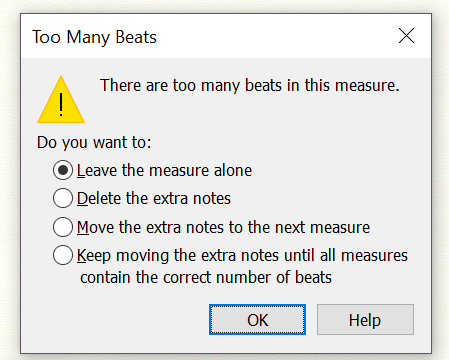

In Dorico I don’t get popups telling me I have “too many notes in a measure.” Enter the note duration you want, at any place you want, and it works.

2. Quickly manipulate notes (or groups of notes) without switching to the mouse

In order for my creative flow to not get bogged down, I want to be able to manipulate, change, and otherwise monkey with notes I’ve just entered. And I don’t want to have to take my hands off the keyboard. In Dorico, I’ve been amazed at how easy that is. By default, any keystroke-combination function applies to the note I just entered, but it’s easy to grab previous notes too with Shift+Left.

Here’s a list of pitch related functions you can instantly perform to notes you’ve just entered:

- Move up or down diatonically

- Move up or down chromatically

- Move up or down by octaves

Here’s a screen grab demonstrating these functions in order. The video isn’t sped up. I went slowly for the sake of demonstration, but it’s easy to be as fast as your fingers (and brain) want.

Or, select a group of notes, and add notes a set interval above or below them:

And you can easily manipulate rhythmic values as well—again, without using the mouse:

- Make a note longer or shorter in increments of your chosen rhythmic grid unit (which you can change)

- Turn straight rhythms into dotted

- Move notes forward or backward, preserving their duration.

There’s plenty more, but these are just the simplest functions. Even though I’m still learning the key commands, I found everything made sense. I enjoyed the creative process. It’s clear the Dorico team has designed the program to accommodate the composer, and this design has been an unexpected delight for the past several weeks.

Set global defaults and stop tweaking

My original reason for considering Dorico wasn’t primarily creative. I knew I didn’t like Finale, but I didn’t have any conception of how it could be different. But what I knew I wanted was to stop making hundreds of tweaks to every score to make it look good. I was tired of rehearsal marks colliding with tempo marks and articulations colliding with slurs. I was tired of moving and nudging and bumping a thousand little boxes. I just wanted to put in the notes and print out the music.

Dorico encourages the user to focus on global settings instead of manual adjustments. The basic idea is to make all the decisions for the score, big, and small, and let Dorico interpret them.

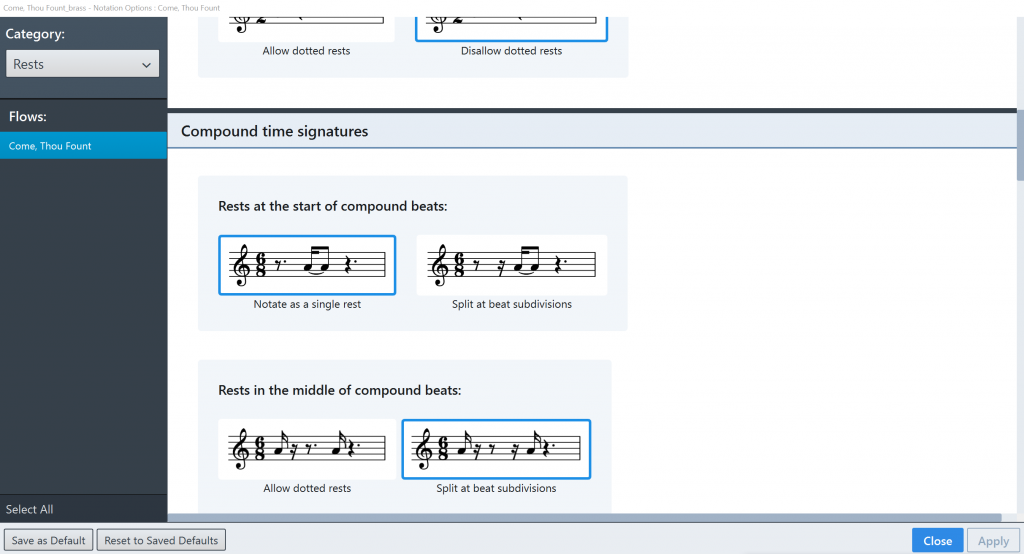

Notation options controls the “big-picture” engraving choices, like how notes are beamed or how rests are displayed:

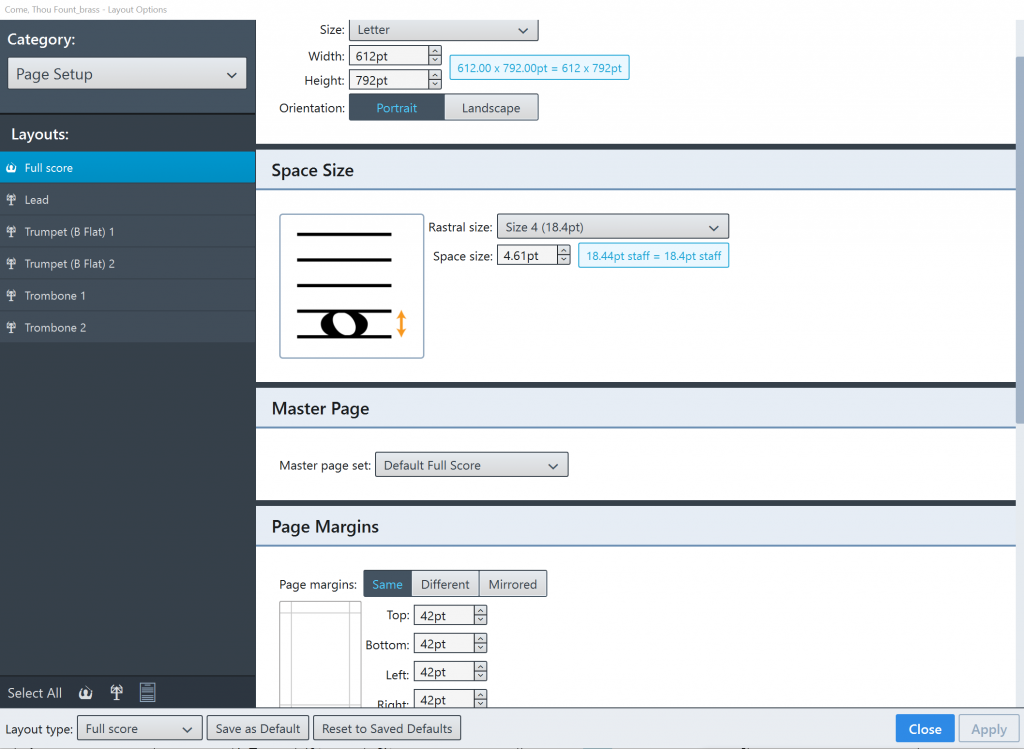

Layout options controls the layout of different parts, and allows you do modify settings for each accordingly:

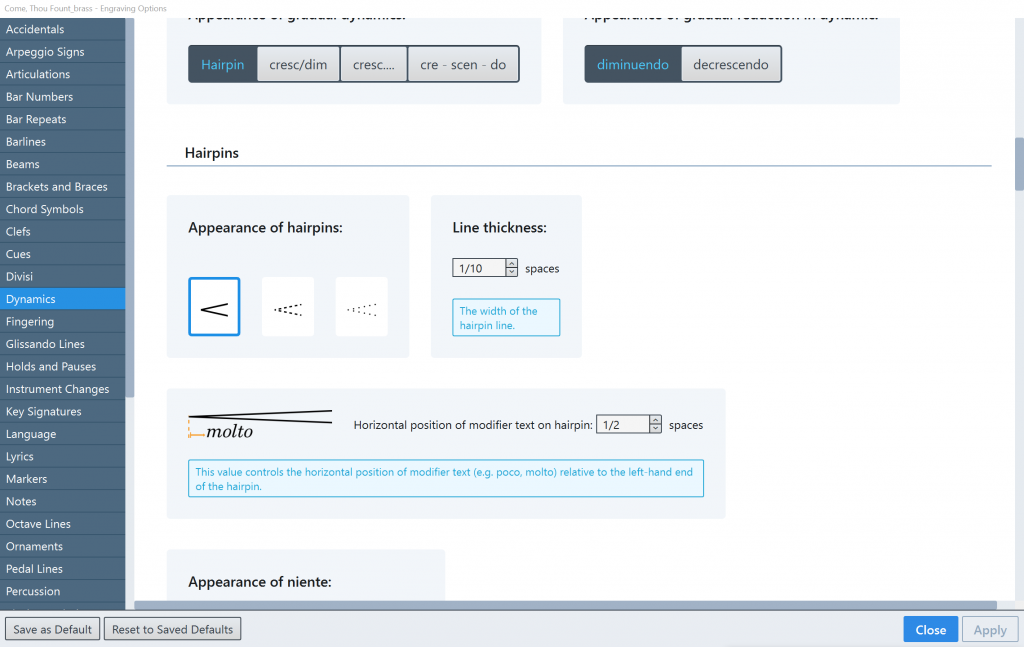

And Engraving Options is everything else: the details of the piece (and it’s quite a comprehensive list):

I love this approach, but I have to admit, old habits die hard. When I finish an arrangement and switch to a part layout, maybe I think the staves are spaced too closely… and my first instinct is to start manually adjusting everything. Don’t do that.

And for every one of these settings, there’s the option to “Save as Default.” So you only have to mess with the settings once, and you’re done. Of course every score requires some tweaking, and Dorico accomodates manual adjustments beautifully. But for my first project—a piece for brass quartet—I think I shifted one item slightly. The rest of my time spent was in the three option menus above, deciding what I liked and setting it as the default for all future projects. Once and done.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that Dorico is just worlds better than Finale. And the development pace is astonishing. Yes, there are small bugs here and there. But even as a young program, it’s far superior in terms of workflow, efficiency, and output. I collaborate with a number of fellow musicians who still use Finale, and already I dread the thought of going back.

So yes, I do have an ulterior motive for reviewing Dorico so positively. I want people to switch, because I want Dorico to succeed. The reality is that Finale (and to a lesser extent, Sibelius) have a solid grip on the market. Most people are deeply entrenched. Other notation programs aren’t dying anytime soon, and that’s fine. Competition is good. After all, MakeMusic has demonstrated what complacency does to innovation. But Dorico deserves at least an equal shot.

Watch the tutorials, download the 30-day trial, and be willing to relearn your workflow. There’s a cross-grade offer for Finale users. Take the long view. Do you really want to be monkeying with articulation collision for the next ten years? Is that your hobby? Or is it actually making beautiful scores that people can use for making music?

Old dog, new tricks. Or perhaps the better word would be “tools.”