The following is an appeal to my believing friends who are poets, composers, lyricists, and various iterations of wordsmiths.

Watts’ Burden

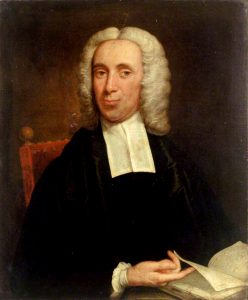

Isaac Watts (1674-1748). © Hackney Museum, Chalmers Bequest; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

My opening volley (and I’ll need only one) is an excerpt from the preface of Isaac Watts’ Divine and Moral Songs for Children, 1720. This is the publication and the author that gave us “I Sing the Mighty Power of God”— hardly on the same level as “Deep and Wide.” It is solemnly addressed “to all that are concerned in the education of children.”

“MY FRIENDS,

“It is an awful and important charge that is committed to you. The wisdom and welfare of the succeeding generation are entrusted with you before hand, and depend much on your conduct. The seeds of misery or happiness in this world, and that to come, are oftentimes sown very early; and, therefore, whatever may conduce to give the minds of children a relish for virtue and religion ought in the first place, to be proposed to you.

“Verse was at first designed for the service of God, though it hath been wretchedly abused since. The ancients among the Jews and the heathens taught their children and disciples the precepts of morality and worship in verse. The children of Israel were commanded to learn the words of the song of Moses, Deut. 31:19,30; and we are directed in the New Testament, not only to sing, “with grace in the heart,” but to “teach and admonish one another by hymns and songs,” Ephes. 5:19. And there are these advantages in it:

- There is a great delight in the very learning of truths and duties this way. There is something so amusing and entertaining in rhymes and meter that will incline children to make this part of their business a diversion…

- What is learned in verse is longer retained in memory, and sooner recollected. The like sounds and the like number of syllables exceedingly assist the remembrance. And it may often happen that the end of a song, running in the mind, may be an effectual means to keep off some temptations, or to incline to some duty, when a word of scripture is not upon their thoughts.

- This will be a constant furniture for the minds of children, that they may have something to think upon when alone, and sing over to themselves. This may sometimes give their thoughts a divine turn, and raise a young meditation. Thus they will not be forced to seek relief for an emptiness of mind out of the loose and dangerous sonnets of the age.”

I trust you’re sufficiently compelled upon reading that, as I was. Now to the matter at hand: what should our children be singing?

Tradition, Skill, Priorities

Why do such songs as “Father Abraham” and “I’m in the Lord’s Army” continue to endure in spite of their triviality? Simple: they’re familiar. If called upon to lead children in singing, most people will default to what they know— that is, what they grew up singing. But children, as everyone knows, are quick studies. They’ll learn to sing whatever we teach them. We are the ones who shape traditions for them.

Of course children should sing the same hymns as their parents. But there’s also a place, I believe, for children’s songs that are simple and short. There have been a number of projects to set Scripture to music for children, especially in the past fifteen years. But in my opinion, none have rivaled “Hide ‘Em In Your Heart” by Steve Green. The melodies are simple and singable, the scope is short (usually one or two Scripture verses per song), and the recordings are actually sung by children. Unlike most modern attempts at such a project, “Hide ‘Em In Your Heart” relies on melody instead of rhythm, and I believe this is its greatest strength.

It’s not easy to turn a Scripture passage into a simple, memorable song. It requires a lyricist’s attention to cadence and poetic meter. It’s a unique skill, not unlike the brilliance of Disney or Broadway writers— but in this case, bent towards an eternal purpose.

We’re all busy, and there are a hundred projects we could spend our time on. Go back and read Watts’ preface again, and tell me if this shouldn’t be at the top of the list for believing musicians.

The Vision

Here’s what I’m proposing:

- short, simple songs that are a mix of Scripture verbatim and paraphrased, with little poetic license. I think the Steve Green album I mentioned is a superb model.

- real melodies, not overly-syncopated pop drones. Complex or subtle rhythms won’t translate easily to acappella and quickly become outdated, but good melodies will always wear well.

- for these to become ingrained in the minds of children and parents and teachers, they’ll need a good recording. It has to be pleasant to listen to repeatedly: well-produced, varied in instrumentation, and preferably led by children’s voices, sung in a sweet and simple head voice. No yelling.

So I’m appealing to my friends who are wordsmiths. I know that some of you view a skillfully-turned phrase as a work of art. If the Word is already dwelling in you richly, it’s a short step to join the two. Will you consider trying your hand at versifying Scripture for the next generation of the church?